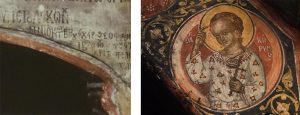

St Mercurius, detail with the signature of Michael Astrapas on the sword, wall paintings from the church of the Virgin Peribleptos, Ohrid, 1295, photo Ivan Vanev

What do we know about the working practises of these masters, how did they obtain their knowledge and master their skills, to what extent was their work valuable and what was their status in the society? These are questions to which we still have a few answers in science, but which inevitably accompany the specialist interested in Orthodox art.

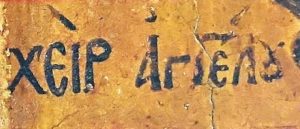

Where do we draw information about these questions from? First and foremost, from written sources of any nature as the most important among them are the signatures of the icon-painters left in different parts of the murals and icons made by them but also from any other kind of written evidence and documents from the respective age. But even in the cases where they did sign we know nothing about these icon-painters but their names and in practice a small percent of the Byzantine icons and murals that have survived to this day are signed. For a period of eleven centuries – between the 4th and the mid-15th centuries – the researchers have gathered just about 100 names of masters, two-thirds of whom are painters. The difference in the quantitative indicators in terms of the number of preserved names of icon and mural masters in different centuries of the pre-Modern epoch compared to the ones in the Byzantine Empire is impressive. More than 2000 names of Greek icon-painters from the 15th-18th century are known to the specialists, although in many cases such names are evidenced only from documents. As regards the Serbian material these numbers look different: a total of 50 something masters who created icons, murals and miniatures in that period. For comparison, the data from the monuments on Bulgarian territory are nothing short of scarce: less than 20 names of icon-painters from the period 15th-17th century have reached us. And yet it should be noted that the number of signed icons and mural ensembles does not exceed one-third of all monuments that have been preserved to this date, i.e. in their major part this occupation still remained anonymous in 15th-17th centuries.

The signature of the Cretan icon painter Angelos, photo according Milanou, K., Ch. Vourvopoulou, L. Vranopoulou, A.-E. Kalliga, Angelos’s Painting Technique …, ill. 1

The quantitative parameters listed illustrate the continuous process in the change of mind and self-esteem of the Late Medieval icon-painter. In the very end of the 17th century he could already not only leave his name on his works, often in the churches’ ktetor’s inscriptions themselves but also perpetuate his portrait in the murals he painted on the interior of the church, as Pârvu Mutu did in 1692 in the Church of Trei Ierarhi in Filipestii de Padure in Wallachia. Nevertheless, the Wallachian painter Pârvu Mutu is an exception for the period and one can say that by and large in Late Middle Ages the icon-painters on the Balkans continued to demonstrate their humility and God-fearing. Thus, in the cases where we see their names on murals and icons they are often accompanies by attributes such as “the sinful”, “of many sins”, “the unworthy” servant of God, a practice we know well from the preceding epoch. It is evident from the preserved materials that there is still a long way to go before they get the self-confidence of the Revival master so vividly demonstrated by Zahari Zograf.

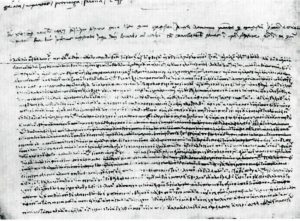

What we know about the painters’ working arrangements and acquisition of skills in the period 15th-17th centuries on the Balkans is relatively conditional. As the scientists see analogies between the work of painters and the work of other craftsmen it is assumed that the workflow was organized following the logic of the other crafts. It was done by a group of people among whom there were leaders – i.e. the masters, and assistants, i.e. the apprentices and students but it seems there are no preserved Byzantine written sources commenting on those aspects. All documents mentioning the existence of studios with a chief master and assistants of the type of Western artists’ studios refer to the practice of the Republic of Ragusa and on the island of Crete. In the State Archives of Venice and Dubrovnik are preserved written contracts for performance of commissions in which the terms, payment and provision of materials are agreed upon as well as contracts for training, which usually lasted from one to ten years.

Self-portrait by the painter Pârvu Mutu, fresco fragment from the church in Bordeşti (Vrancea County), 1699, today in The National Museum of Art of Romania, Inv. 1513.

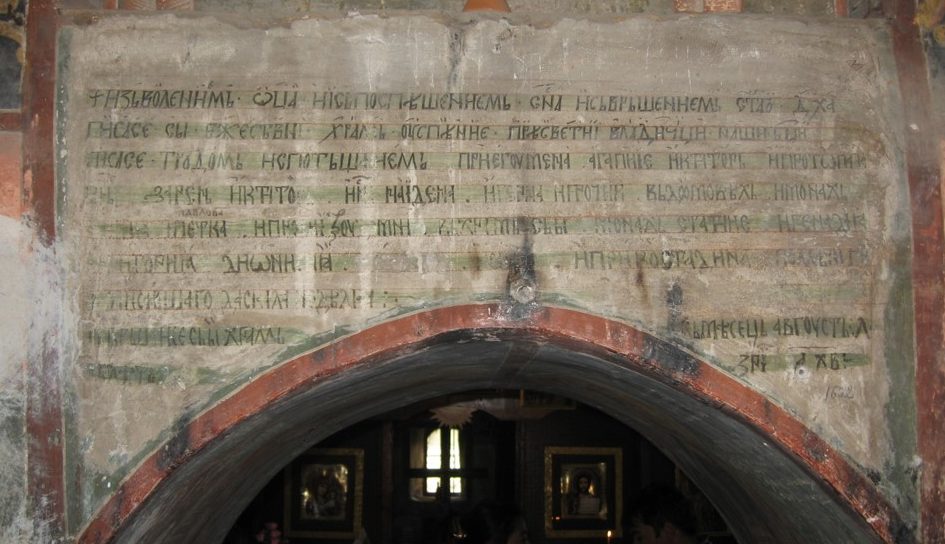

How exactly the icon-painters on the Balkans organized their work, how they handed down the knowledge and what their status was in the territories under Ottoman rule is, however, far from clear in such detail because there are not so many written sources that have reached us. We draw some information about the icon-painter in these areas mainly from the donor, invocation or other type of inscriptions preserved on murals and icons, and more rarely from notes in manuscripts from the period, from the monastery beadrolls or travelers’ records. What processes took place in the lands of the Balkans conquered by the Ottomans and under what conditions did the icon-painters work here? Without playing down the specifics of different regions of the peninsula and the specific historical events in those centuries that are decisive also for the characteristics of the artistic production some most general aspects can be outlined. First and foremost, it is about master craftsmen who existed and made their living as part of the population subjected to the Ottoman rule. Without exaggerating the scale of the negative sides of that position we should nevertheless note the greater difficulties encountered by those icon-painters. Sometimes they were also echoed in the inscriptions in the murals of the churches from the period such as for example the Lomnica monastery in today’s Bosnia and Herzegovina, where in the ktetor’s inscription from 1607/8 the icon-painters Ioan, Nikola, Georgi and one more Ioan asked not to be blamed for possible errors because they worked in great fear of the Turks and “of much other evil”. The wording “painted at needed time” which is repeated in the murals of the Alino Monastery from 1626 and in the Church of St. Paraskeva in the village of Selnik in today’s Macedonia which were made by the same master is also interpreted as an echo of the hard living conditions.

On the other hand, historians view the 15th-17th century on the Balkans as times of intense interethnic contacts which were carried out under specific historical conditions: the absence of state borders in the interior of the peninsula for a long historical period which facilitated the mobility in space; the multiethnic character typical of the Ottoman empire; the mass migration of big groups of population because of military operations or as a result of special campaigns organized by the state authorities; linguistic interaction between populations migrating not only from one region to another but also from villages to towns as part of such process of migration is the seasonal work, traveling to work abroad or occupation in stock-breeding of semi-nomadic nature; and mostly the emphasis on faith as the unifying factor for the Orthodox people against the background of the presence of different religion and Ottoman colonization policy. Under these conditions people of different ethnic origin speaking different languages lived together in the same place and communicated between one another as such communication was part of a much boarder process of cultural interaction. Thus, it is not a rarity for the epoch that several languages were used simultaneously, and this is especially true for the mobile groups of the society such as merchants, representatives of high clergy, men of letters and also icon-painters. It is difficult to determine to what extent the icon-painters had command of written foreign languages. The level of education in that epoch varies greatly but the monuments preserving bilingual epigraphic materials provide an opportunity for speculation in such direction. On the other hand, the rare cases where the icon-painters explicitly defined their nationality, which happened mostly when they worked in another environment remote from the place they come from should be pointed out. Among the examples one can mention Necratios the Serb, born in Veles, who made murals and icons for the Monastery of Supraśl near Białystok in Poland in mid 16th century, or the copyist and miniaturist Lazar the Bulgarian who worked at the monastery of Žitomislić in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the early 18th century.

The beginning of the hand-written text of the will of the Cretan painter Angelos Akotantos, made before his journey to Constantinople in 1436, in which he leaves his possessions to his unborn child including a collection of preparatory drawings in case it is male and wishes to continue his craft, photo according Vassilaki, M. The Painter Angelos and the Icon Painting in Venetian Crete …, fig. 3.1.

As also evident from these data the great mobility of icon-painters is typical of the period. The painters Xenos Digenis, Theophanes, Zorzis moved from Crete to continental Greece. A master who is very active in the period is Frangos Katelanos who came from Thebes in Boeotia but his work can be traced for several decades in Ioannina, Kastoria, Kozani, Aetolia, in Meteora and on Mount Athos. This mobility also refers to the following century when masters from the villages of Gramosta and Linotopi in Northern Greece also worked in other places on the Balkans as they often stated in the inscriptions their place of birth. The icon-painters of local origin in the Serbian territories also traveled a lot in different regions of the Patriarchate of Peć. Thus, Longin worked in the second half of 16th century in today’s Eastern Bosnia, Kosovo and Montenegro, in the next century Georgije Mitrofanović moved between Mount Athos, today’s Croatia, Montenegro and Serbia and the centre of the Patriarchate of Peć. In addition to mobility, a principal characteristic of the epoch is also working in mixed teams as the researchers judge from bilingual inscriptions in a number of mural ensembles from that period of the cooperation between non-resident Greek masters with local icon-painters.

The question of how educated the painters were, what exactly the level of their literacy was also presents a heterogeneous picture. In that later period too many icon-painters were clerics of the lower Church hierarchy which presumes that they differed from the barely literate and illiterate part of the population. There are also many cases where the icon-painters were simultaneously men of letters. A special example in the epoch is the Serbian master Longin who was not only a highly-appreciated painter but also a man of letters with literary talent and his own works. Doing different jobs in the field of art simultaneously whereupon a master had the abilities to make icons and murals and at the same time to copy and decorate books which also happened in the preceding epoch occurred among the best ones. In the 17th century and early 18th century the predicate “daskal” sometimes appear with the name of the icon-painters in the inscriptions they left, which is interpreted by some researchers as an indication that in addition to the subtleties of their craft they also taught reading and writing.

Donors’ inscription from the catholicon of the Monastery of St Nicholas Anapafsas, 1527, with the signature of Theophanes the Cretan, photo according Τσιγαρίδας, Ε. Θεοφάνης ο Κρης …, 108, ill. 19, and St Cyricus, wall paintings from the same monastery, photo Ivan Vanev

These masters’ work is seasonal. From the ktetor’s inscriptions it is obvious that most churches were painted in the period from April to October as these months are more appropriate for the making of murals due to the technological peculiarities of the job and the weather in that part of the year enabled the icon-painters and their teams to move more easily. Naturally, this job depends on the climate characteristics of the place where it is done and where the weather so allowed the churches could be painted year-round as the practice on the island of Crete seems to have been. In the same way one can fairly speak of the speed at which the mural-painters worked which depended both on their number, abilities and qualification and on the specific conditions of the commission, the size of the church, the funding, etc. In winter the master painters are thought to have fulfilled the commissions for icons or manuscript decoration.

Similarly to the Byzantine Empire and the remaining Orthodox world it seems that on the Balkans in 15th-17th century the skills of the master icon-painters and especially of the mural-painters were acquired for a long period of time whereas in major part of the cases the knowledge was handed down within a close circle of relatives, commonly from father to son or some close relatives –– a normal succession in most professions as early as in the Middle Ages. The matter concerns truly complex knowledge. Preparation of plaster with lime and filling agents such as straw, sand, ground bricks, mixing the pigments, binding agents and the manner of paint laying on different bases, the making of brushes – these all require technological knowledge, and if the ability to paint freehand acquired mostly by incessant copying of old patterns is added to them it becomes clear that this is a set of specific skills requiring long training and a good master to hand down the subtleties of the trade. In addition to the technical skills related to the creation of the artistic image the icon-painters and mural-painters, both in the Byzantine Empire and on the Balkans in the pre-Modern epoch, also acquired certain set of iconographic solutions for different compositions and types to reproduce them when fulfilling their commissions. The main part of the iconographic patterns was handed down from teacher to student as in the course of time, depending on the individual abilities and the opportunities provided by the fate of traveling and seeing older patterns each icon-painter enriched his knowledge or changed his preferences.

The Serbian master Longin is among the rare examples of a highly educated person of his time: he was a monk and man of letters, a skilful icon-painter and author of frescoes. Here are reproduced some of his works: a fresco from the narthex of the Patriarchate of Peć Monastery (1565), an icon for the iconostasis of the Lomnica Monastery (1579), a miniature from the Krušedol Gospels and a page of his manuscript with his Akathist of St Stephen, photo according Тодић, Б. Српски сликари … и Шпадијер, И., Б. Тодић. Појава свестраних …, 565-573.

Some masters had a more global influence on the artistic processes in the epoch. Cretan icon-painters Angelos Akotantos and Andreas Ritzos combined in a specific manner some samples of Byzantine art of the capital city with influences from Western painting, and the most famous Cretan master, Theophanes Bathas, while working at some monastic centers important for the epoch such as Meteora and Mount Athos, transferred the iconographic solutions and style typical of Crete to the Balkans, leaving a significant mark in the artistic field long after his death. Part of the Cretans’ models were used in the middle and in the second half of 16th century by the Epirus icon-painters who are mentioned in the art studies as ones belonging to the so-called “school of Northwerstern Greece” or “school of Epirus”, some of whom we know by name: Frangos Katelanos and the Kondaris brothers. They also reproduced individual scenes and iconographic elements of local tradition as evidenced from the production of the masters of the “Ohrid School” and “Kastoria ateliers” by making their own innovations as well. Both Cretan and Epirote influences can be noticed in late 16th century and in the 17th century in the work of the icon-painters from the populated areas in the slopes of the Gramos Mountain in Northwestern Greece – Gramosta and Linotopi – but also in many other places on the Balkans, especially in monuments made by Greek masters. In this type of succession of the patterns the influence of different degree of Western painting should also be noted in all groups of icon-painters from continental Greece. All of this outline quite a complex picture in icon-painting and murals, especially in the second half of the 17th century on the Balkans when iconographic solutions of diverse origins might be used in the same work.

Donors’ inscription from the Holy Virgin church, Karlukovski Monastery, 1602, with the name of the icon painter „daskal“ Nedelko, photo Ivan Vanev

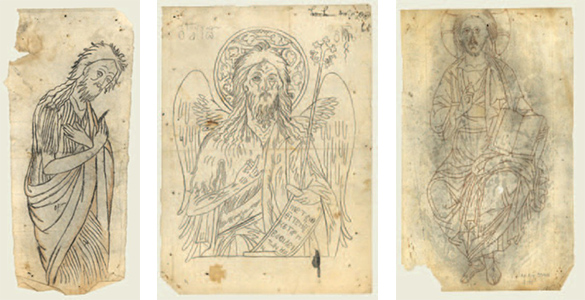

At this point we get to another crucial question related to the peculiarities of the work of the Late Medieval icon-painters, and namely: how did they store the information about their patterns and how did they reproduce them in their works, whether they used copies made by them as preliminary drawings, templates, or collections of such models? In several world libraries and museums there are collections preserved with preliminary sketches on paper made by East Orthodox masters, dating back mostly from the period 17th-19th century. The biggest of these collections is kept at Benaki Museum in Athens. The study of that collection shows that individual counterparts contain traces of use – punching and pigmentation in certain places – which means they were used when making the icons. On the other hand, several rare examples have been preserved of individual manuscripts from earlier time with drawing samples which seem to have been created for master icon-painters’ personal use. When studying such materials, the researchers have arrived at the hypothesis that the Late Medieval icon-painter memorized multiple images by constantly painting and copying and the preserved examples are merely a testimony of that process of visual memory training via mnemotechnical methods such as verbal descriptions, for example, and not proof of an organized system of creating and using books with samples in the Byzantine Empire. It is no chance that in the manuals for icon-painters we see precisely a verbal description of how the compositions and saints should be depicted in the church. As a whole the examples of freehand drawings in manuscripts, sketches and samples preserved at museum collections as well as the instructions on how to copy old samples in the manuals for icon-painters show that some preliminary drawings or collections of certain iconographic patterns might have been used when making murals as well. It is not very likely that these were copy papers to scale, which are unpractical because they had to be remade for each mural ensemble again and again and also unprofitable in economic terms given the still high prices of raw materials such as parchment and paper in the period 15th-17th c.

Icon painters’ drawings on paper in the form of pricked cartoons, 17th c., part of the collection of the Benaki Museum, Inv. No 33154 (Ξ 17Α), 33200 (Ξ 49Α), 33411 (Ξ 195), photo according Vassilaki, M. Working Drawings … .

Undoubtedly, far from every painter during the epoch possessed the set of qualities typical of the big masters but the specific characteristics of this occupation were preserved. As people creating the sacred images highly-esteemed in those centuries the icon-painters continued to occupy a special place on the borderline between craft production and the spiritual realm.

References

Божков, А. Творческият метод на българския художник от епохата на турското робство до Възраждането. – Известия на Института за изобразителни изкуства, Х, 1967, 5-32.

Божков, А. Социалната и творческата природа на българския зограф от Средновековието. – Изкуство, 5, 1976, 10-17.

Гергова, И. Нови факти за началото на живописта в Трявна. – Изкуство, 3-4, 1978, 72-74.

Божков, А. Българската икона. С., 1984(по-специално гл. 3: Създателите на българската икона, 177-319).

Χατζηδάκης, Μ. Έλληνες ζωγράφοι μετά την Άλωση. Τόμος 1. Αθήνα, 1987.

St Luke the icon painter, wall paintings from the catholicon of the Driovouno Monastery, Greece, 1652, photo Ivan Vanev

Garidis, M. La peinture murale dans le monde orthodoxe après la chute de Byzance (1450-1600) et dans les pays sous domination etrangère. Athènes, 1989.

Пенкова, Б. Към въпроса за творческия процес на средновековните зографи (Някои наблюдения върху стенописите на Роженския манастир). – Изкуство, 5, 1989, 36-41.

Смядовски, С. Чин над иконописцем. – Проблеми на изкуството, 2, 1996, 20-22.

Гергова, И. Зограф Иоан от Чивинодола. – Проблеми на изкуството, 2 1997, 31-40.

Χατζηδάκης Μ., Ε. Δρακοπούλου. Έλληνες ζωγράφοι μετά την Άλωση. Τόμος 2. Αθήνα, 1997.

Пенкова, Б. За някои особености на поствизантийското изкуство в България. – Проблеми на изкуството, 1, 1999, 3-8.

Δρακοπούλου, Ε. Ζωγράφοι από τον ελληνικό στον βαλκανικό χώρο: οι όροι της υποδοχής και της αποδοχής. – In: Ζητήματα Μεταβυζαντινής Ζωγραφικής στη μνήμη του Μανόλη Χατζηδάκη. ed. Ευγενία Δρακοπούλου. Athens, 2002, 101-139.

Тодић, Б. Лични записи сликара. – В: Приватни живот у српским земљама средњег века. Eds. Марјановић-Душанић, С., Д. Поповић. Београд, 2004, 493-524.

Βαφειάδης, Κ. Η οργάνωση των εργαστηρίων ζωγραφικής και οι όροι της καλλιτεχνικής δημιουργίας στο Βυζάντιο 10ος-15ος αι.). 2004 (http://3gym-kerats.att.sch.gr/library/spip.php?article3, последно посетен 20.06.2018).

Гергова, И. Зографът като писател и читател. – В: Филология. История. Изкуствознание. Сборник изследвания в чест на проф. дфн. Стефан Смядовски. С., 2010, 269-287.

Δρακοπούλου, Ε. Έλληνες Ζωγράφοι μετά την Άλωση (1450-180). Τόμος 3. Αθήνα, 2010.

Тодић, Б. Српски сликари од XIV до XVIII века: књига I, II. Београд, 2013.

Vassilaki, M. Working Drawings of Icon Painters after the Fall of Constantinopolis. The Andreas Xyngopoulos portfolio at the Benaki Museum. Athens, 2015.

Сапунджиева, В. Зографи отвъд границите. Възникването на Тревненската школа в контекста на балканското изкуство ХVII-XVIII в. С., 2016.

Chouliaras, I. Painters’ Cultural and Professional Status as Revealed by the Monumental Inscriptions of Epirus (16th–17thc.). – In: Inscriptions in the Byzantine and Post-Byzantine History and History of Art. Proceedings of the International Symposium „Inscriptions: Their Contribution to the Byzantine and Post-Byzantine History and History of Art” (Ioannina, June 26-27, 2015). Ed. Ch. Stavrakos. Wiesbaden, 2016, 79-94.