View of the church building from south-east

The monastery can be reached from the district of Seslavtsi, at some 18 km from Sofia. The beginning of the road from the village to the monastery is asphalt-paved and ends at the semi-destroyed buildings of the now closed uranium mine Deveti Septemvri, part of Buhovo mine. There follows a short unpaved but still passable road leading to the monastery church. The church is usually locked but the visitors can take the key from the city hall of Seslavtsi. Located in the territory of the mine, the monastery is surrounded by mounds of thousands of cubic meters of grey dirt dug in the search of the Radon deposits. The remains of the mining technology characterize the landscape of the entire region. There is also a tourist route whose marked path connects the monasteries of Seslavsti, Kremikovtsi, and Buhovo.

Christ Pantocrator from the wall paintings of the barrel vault of the naos

There is no data about the time of the establishment of the monastery or its early history. The church was built probably in the beginning of the 17th c. on the remains of an earlier temple, which were discovered in archeological drillings. It is decorated with painting from 1616 made with the donation of hieromonk Daniel and local villagers, as witnessed by the donor’s inscription on the western wall of the naos. In 1618 at the request of the same hieromonk Daniel for the needs of the monastery St. Pimen of Zograph copied and sent to the monastery a Menologion for the month of November; the manuscript with the marginal note, revealing this information, is kept at the National Library. In the end of the 18th c. the Seslavtsi monastery was devastated by Kardzhalii and was deserted until the beginning of the 1830s, when according to the existing sources it became active again. A big role in its restoration might have been played by hegumen Isaiah who is mentioned in marginal notes from the 1830s, preserved in various liturgical books.

The monastery was deserted again in the 1950s because of the opening of the Seslavtsi Uranium mine. The monastery was located in the very yard of the mine. Since the zone was hazardous, the access to the monastery was strictly forbidden until 1989. This was a period of decay which continued many years. Until recently the monastery was abandoned, the once preserved remains of housing and farming buildings were torn down; the monastery was repeatedly dug up by treasure hunters. In the last ten years several campaigns to save the monastery and the valuable frescoes in the church were initiated by different state institutions, foundations and private entities and a new door was mounted on the church, the surrounding space was cleaned up and developed. In the place of the ruins of the monastery buildings there are now a shed and tables with benches. Unfortunately the development works in the church surroundings, the use of concrete, cement and tin, have damaged the original outlook of the monastery; the authentic monastery atmosphere has been lost.

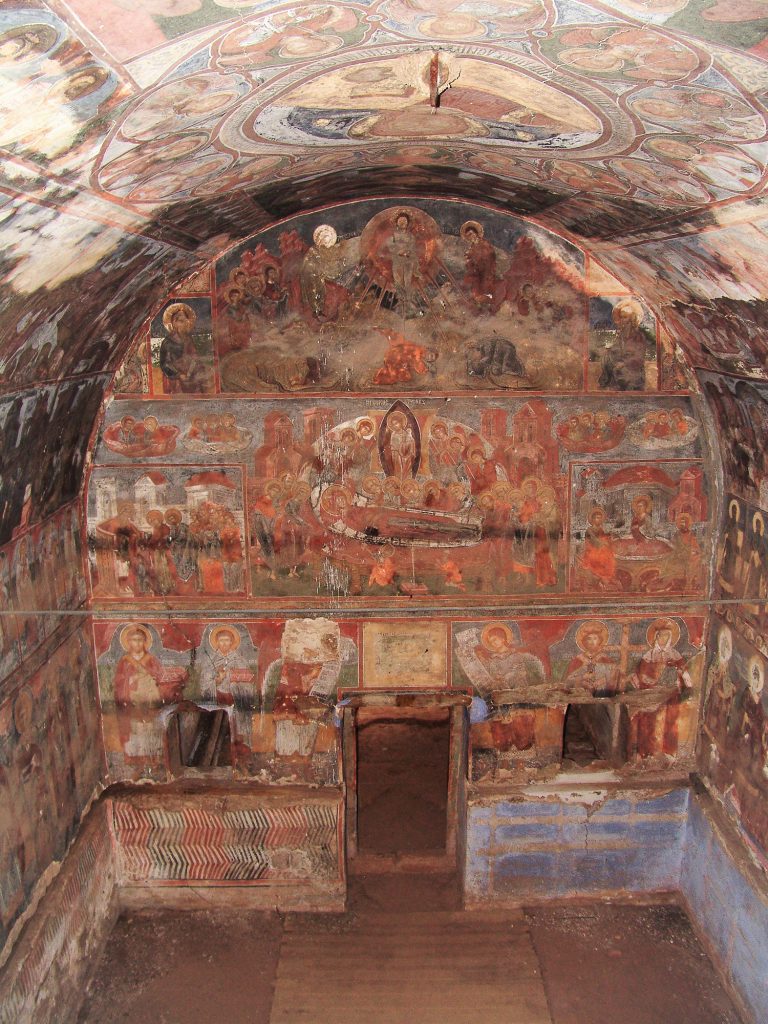

Wall paintings from the west part of the naos

From the old monastery complex only the church still stands today. It is a single-nave building with one apse and a narthex, but it is higher and wider as compared to the rest of the surviving churches in the region from the same period. It is built in rubble masonry, the facades are decorated with a tooth brickwork cornice under the roof; the entrance is decorated with three rosettas.

The church presents several painting layers, mainly dating from 1616 and from the 1830s, when the images of the saints on the low part of the northern wall of the naos were painted over. The murals on the western, the eastern and the southern facades are almost completely destroyed, which makes a well-grounded dating almost impossible. There is evidence of demounted fragments of paintings from the other monastery buildings, probably from the refectory, which are kept at the National Museum of History and probably date from the 17th c., but they don’t seem to coincide in style with the 1616 layer. The 19th-c. frescoes were made by the Samokov icon-painter Kosta Valyov.

Description

In the altar apse there is an image of Theotokos with two archangels, underneath unfolds the composition of the Divine Liturgy and in the lowest register are the Officiating Church Fathers. In the vault (east) there is a depiction of Christ from the Ascension scene, as well as medallions with the divine hypostases: Christ Emmanuel, Pantocrator and Angel of the Great Council. As usual in most painting programs from the period these images are flanked from the south and from the north by half-length of Old Testament prophets holding scrolls with texts. Under the scenes of the Great Feasts are presented the Miracles of Christ, unfolding on the northern and on the southern walls оf the naos. Their order follows the order of the liturgy and the Sundays following the Resurrection of Christ. Among them are the relatively more rare scenes of Christ exorcising seven demons from Mary Magdalene on the southern wall, Christ healing the blind, lame and lepers and Christ healing the deaf, lame and paralyzed on the northern wall. The frieze of medallions and busts of saints, which is almost always present in the decoration of the churches of that period, here has been replaced by a register with full-length figures of saints, presented in smaller size, among whom bishops, archbishops, and patriarchs, and in the lowest zone can be seen the usual full-length figures of saints, fathers of the church and warrior and healer saints. Especially interesting are the images of St. George the New of Sofia and St. Nicholas the New of Sofia from the lowest register with saints on the northern wall, part of the over-painting of the 19th c. and which are supposed to repeat the earlier layer.

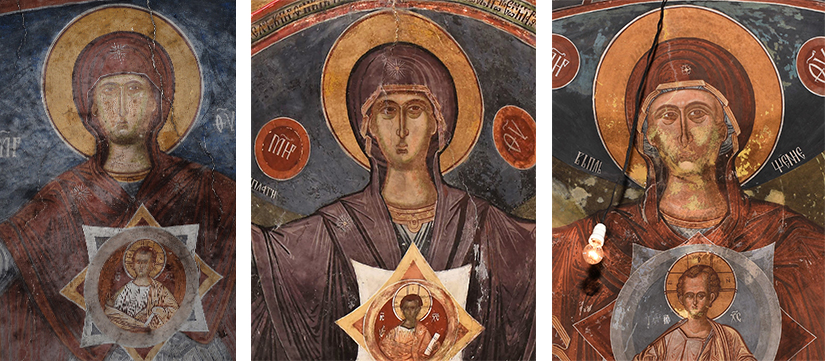

The images of the Mother of God with the Child from the wall paintings of the apses in the Seslavtsi Monastery, the church in Zervat and Slimnitsa Monastery

The paintings in the vault are also interestingly situated. In rectangular fields have been depicted three groups of full-length figures: Mother of God and archangels Michael and Gabriel, prophets Daniel, Zachariah and St. John Prodromos, as well as prophets Malachias, Elijah and Moses. On the eastern wall of the narthex, following the curve of the vault, is depicted Jacob’s Ladder. Under it is the patron niche with the image of St. Nicholas, surrounded by scenes of the Akathist to the Theotokos, which continue on the northern and the southern walls, illustrating the oikoi and the kontakia in two registers of scenes. On the western wall of the narthex is developed another composition relatively uncommon for our 17th c. monuments – the Tree of Jesse. High above it at both sides are depicted the hymn-writers St. John of Damascus and St. Cosmas of Maiuma. To the impressively rich repertoire of saints in the temple, the narthex adds the images of monks and hermits, related with the church function. Quite impressive is the compact group of Balkan saints: Prochoris of Pcinja, Joachim of Sarandapor, Gabriel of Lesnovo, depicted on the western wall, as well as St. John of Rila on the southern wall of the narthex.

There are also images of women saints among whom St. Thekla, St. Marina, St. Varvara. St. Catherine, and St. Petka, which is determined by the liturgical function of this space, probably intended for women.

Similarities in the types with repetitive features used in the wall paintings in Seslavtsi Monastery (1 and 2), the church in Zervat (3) and Slimnitsa Monastery (4 and 5)

Cyrillic and Greek.

The frescoes of 1616 at the monastery church in Seslavtsi are made by a single team of two leading icon-painters, working simultaneously in the naos and in the narthex. The painting in the naos and especially the frescoes on the vault are made by the better trained icon-painter.

A typical vessel, which can be seen in the wall paintings of the Seslavtsi Monastery (1 and 2) and in the church in Zervat village (3)

The development of the decorative program of the Seslavsti monastery church is hypothetically attributed to the so-called Pimen’s Atelier but this hypothesis is hard to prove since no signed works of Pimen Zografski (Sofiiski) survive that could be used in this comparison. Far more well-grounded appears the opinion that the closest parallel of the Seslavtsi paintings are the murals in the church of St. Theodore Tyron and St. Theodore Stratelates in the village of Dobarsko of 1614 and that earlier closest analogies can be found in the eastern part of The Dormition Church in Zervat (Albania) of 1605/06 and in the naos of the Slimnitsa Monastery of 1606/7. We are speaking of one atelier which – even though changing its staff – has worked on these and on other sites in the end of the 16th c, and the first quarter of the 17th c. in the Balkans.

Margarita Kuyumdzhieva

Каменова, Д. Сеславската църква. История, архитектура, живопис. София, 1977.

Прашков, Л. Е. Бакалова, С. Бояджиев, Манастирите в България. София, 1992.

Куюмджиев А., Б. Пенкова, Г. Геров, Е. Бакалова, И. Ванев, И. Гергова, М. Куюмджиева, Ц. Кунева, Ю. Бойчева. Корпус на стенописите от XVII век в България. София, 2012 (автор на статията за паметника е И. Гергова)

Василев, Ц. Гръцкият език в църквите със смесени надписи от XVII век в България. София 2017.