Archangel Gabriel, St. Nicetas near Čučer (1483/4)

The upsurge of the Kastoria ateliers in the last decades of the 15th c. was the result of different factors: the favorable geographic location of the town which is aside from the main routes of the conqueror, the decline of the Balkan states after the Ottoman invasion, the artistic tradition of Kastoria of the previous centuries. The location of the town-peninsula at the Kastoria Lake and near the big river Aliakmon (Bistritsa), which connects it with Thessaloniki and hence with Constantinople, is also crucial. On the other hand, the closeness of the town to main trade roads prompted the active trade and cultural exchange with the rest of the Balkans.

Together with the strategic location of Kastoria, another very important fact stands out: the town is the seat of one of the main bishoprics of the Ohrid archbishopric, which helped Kastoria keep its traditions alive.

The role of some personages is often stated to be the main reason for the appearance of the Kastoria icon-painting ateliers: the first Tsarigrad patriarch after the fall of Constantinople in 1453 Genadius Scholarius, the daughter of Georgi Brankovic and wife of sultan Murat II and mother of Mehmed II the Conqueror Mara Brankovic or the especially talented anonymous icon-painter who founded a big atelier in a very short time.

Viktorija Popovska-Korobar believes that the shared iconographic features of the Kastoria monuments and the works of the Ohrid artistic school of the 15th c. appeared because the two centers are different manifestations of the activity of a single school with a main center in Ohrid. Gojko Subotić suggests that these similarities stem from a common root in a broader sense.

On the territory of the present day Greece, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Serbia, and Albania over 50 monuments are preserved that are related with the Kastoria ateliers, dating from the 1480s to the 1530s, most frequently some humble monastery or parish churches. Some scholars suggest that the Kastoria ateliers also operated in Moldavia (Northeastern Romania) but in all probability the numerous iconographic similarities between the Kastoria and some Moldavian monuments are to be explained by the strong influence of the Kastoria masters on the Balkan painting.

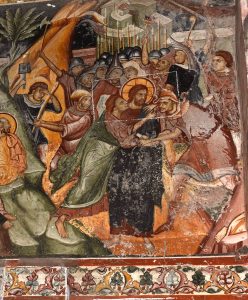

Judas betrayal, Treskavec Monastery (the end of the 15th century)

The publications on the Kastoria artistic production by authors such as Manolis Chatzidakis, Evtimios Tsigaridas, Evangelia Georgitsoyanni, etc. speak of an atelier originating from Northern Greece that worked almost exclusively in Greek lands. Among its representative works are the frescoes of the Old catholicon of the Great Meteor (1483), part of the frescoes in the Treskavec monastery (1483) and the monastery of St. Nicetas near Čučer (1483), in the church of St. Nicholas of nun Eupraxia in Kastoria (1486), in the church of St. George in the monastery of Kremikovtsi (1493), in the church of St. John the Theologian of Poganovo monastery (1499), the Holy Anargyroi Church in Servia (Greece, 1510), etc. But in all these churches are distinguished the handwritings of many different masters; apparently a single atelier couldn’t have worked on so many and so distant sites at the same time, sometimes within the same year.

The thesis of the great Serbian scholar Gojko Subotić about the Kastoria Art School is based on the existing continuity of the Kastoria ateliers from the 11th c. on. However, in order to define a group of artworks as the production of one atelier or one school, one needs to have concrete historical data and clear enough stylistic and iconographic similarities between the works. In this case the interrelations are varied.

In the above mentioned classical monuments from the 1480s are visible several extremely close in style masters (G. Subotić believes that this was the chief icon-painter). The 90s painting also features some very close representative examples – the monastery of Kremikovtsi, some of the paintings in St. Nicholas of archontissa Theologina (end of the 15th c.) and Panagia Kubelidiki (1496), the fragments of St. Spyridon in Kastoria (1490s), the painting in St. Petka in Brajcino (Macedonia, end of the 15th c.), the Poganovo Monastery.

In the beginning of the 16th c. and until the 1530s however a significant ramification of the routes of the Kastoria masters occurred and also of the routes of their disciples, followers and imitators, which are very difficult to trace out. From this period we can certainly point at one Kastoria master whose specific drawing manner is discovered in more than one monument: in St. Nicholas Magaliou in Kastoria (around 1505) and a little later in St. Theodore near Boboshevo. The majority of the works of the local ateliers feature the iconographic but not the stylistic particularities of the representative works of the 80s and of the 90s. This is the case with many Greek monuments in Veria, Servia, Agiani, Koustochori, the Holy Savior Church of the Chebren Monastery on Macedonia (1533), etc.

In the 1530s, the Church of Panagia Mouzeviki in Kastoria (after 1532) was partially painted, and a little while thereafter the church of St. George in Kolusha, Kyustendil, Bulgaria (1530s-1540s). The thesis of the connection between those mural layer of Panagia Mouzeviki with the painting at the Toplički Monastery of St. Nicolas (Macedonia, 1536/7), created by the icon-painter Yoan Teodorov of Gramosta who studied in Kastoria and around whom a circle of masters was also formed subsequently has long since been put forward in the literature. The murals at the Church of St. George in Banjani (the district of Skopje, 1548/9) also belong to his works.

Warrior saints, St. Nicholas Church of Nun Eupraxia, Kastoria (1486)

Therefore, we believe that the terms ‘Kastoria artistic production’ or ‘Kastoria artistic center/circle’ are adequate to the present state of research, when referred to a phenomenon wide-spread in the Balkans.

In these monuments the iconographic specifics are most stable. Without being an invention of the masters of Kastoria, the Deisis compositions with Christ King of Kings and warrior saints, represented as nobles in aristocratic clothing (known as Celestial court) became emblematic of their work. They revived a forgotten iconographic scheme and thus their role besides being borderline can also be called intermediary since through these ateliers many of the artistic techniques of the Paleologian times survived in the following centuries.

Together with the Royal Deesis the constant iconographic features in the monuments of the Kastoria artistic production are present above all in the details and in the secondary motifs. These stable innovations of the 15th c. often represent everyday life elements typical of the period such as attire, armaments, objects, architecture.

In some scenes in great detail are developed the secondary subjects and personages: for example, in the nativity the front is always occupied by a detailed representation of the Bathing of the Child and Joseph’s Doubt; in the Lamentation is present the figure of Nicodemos digging the grave and in the scene of the Myrrhbearers at the Tomb of Christ the group of the sleeping soldiers is very realistic and even comic. As an expression of these trends can be interpreted the scenes of St. Peter’s Denial and of Judas’ Repentance and Suicide, whose iconographic variants characteristic of the Kastoria artistic production highlight their didactic nature.

Archangel Michael, St. George Monastery of Kremikovtsi, detail (1493)

The main stylistic feature standing out against the background of the rest of the post-Byzantine Balkan monuments of the 15th c, is the icon-painters’ attempt to create an illusion of reality. This main characteristic is in the basis of the theory of formation of style as result of the integration of the Byzantine tradition and some western European art elements, mainly from the period of late Gothic style in Italy. Besides including realia, this integration is implemented by means of the ambition to create the illusion of depth and three-dimensionality in the development of the shape and volume of the faces, in the architecture in the background (for example in the typical triangular Gothic arches in the background and on the floors, imitating marble), even in the ornaments.

Royal doors from the church of St. Spyridon, Kastoria (the last quarter of the 15th century, after E. Tsigaridas)

The style and the iconography of the paintings of the Kastoria artistic production as parts of a whole follow a common route of development. The main line is the preservation of the 14th-c. models but not as an imitation but rather rationalized in line with the new historical context and expressed by new artistic means. Through them the painting of the Kastoria icon-painting teams is remarkable for its aristocratism, monumentality, pathos and realism, unique for the 15th c.

Tsveta Kuneva

Main references about the Kastoria artistic production of the 15th-16th cc.

Радоjичић, Св. Jeдна сликарска школа из друге половине ХV века. – В: Радоjичић, Св. Одабрани чланци и студиjе (1933-1978). Београд, 1982, 258-279 (препечатано от Зборник Матице србске за ликовне уметности, 1, 1965, 69-139).

Chatzidakis, M. Aspects de la peinture religeuse dans les Balkans (1300-1550). – In: Chatzidakis, M. Etudes sur la peinture postbyzantine. London, 1976, 177-197.

Tsigaridas, E. Monumental painting in Greek Macedonia during the fifteenth century. – In: Holy image. Holy space. Icons and frescoes from Greece. Athenes, 1988, 54-60.

Γεωργιτσoγιάννη, Ε. Ένα εργαστήριο ανωνύμων του δεύτερου μισού του 15ου αιώνα στα Βαλκάνια και η επίδραση του στη μεταβυζαντινή τέχνη. – Ηπειρωτικά χρονικά, 29, 1988-1989, 145-172.

Суботић, Г. Костурска сликарска школа. Наслеђе и образовање домаћих радионица. – Глас САНУ, СССLXXXIV, Одељење историјских наука, 10, 1998, 109-139.

Terryn, R. Byzantium after Byzantium and the „School” of Kastoria: toward a Corpus of Post-Byzantine Frescoes. – In: Macedonia and the Balkans in the Byzantine Commonwealth. Proceedings of the International Symposium „Days of Justinian I”, Skopje, 18-19 October 2013. Skopje, 2014, 177-185.