Angelos Akotantos, St. Theodore Tyron (middle of the 16th c.), Byzantine Museum, Athens (after M. Acheimastou-Potamianou)

In 1212, the Republic of Venice finally imposed its rule on Crete and the island remained its possession until it was taken by the Turks in 1669. Due to its strategic location Crete is of great importance for the commercial interests of the Republic. The Orthodox population of the island kept their values and traditions but inevitably started to live in a different society where they not only lived together with but were also subjected to the bearers of another, Western, rapidly developing culture. Part of the changes that occurred affected the field of art. The island became a producer and exporter of a great quantity of icons. Their authors were Orthodox icon-painters organized in Western-type studios that fulfilled commissions for both the Orthodox and Catholic inhabitants of the island. Their icons spread out to the other territories populated by Greeks under the rule of the Republic in the Mediterranean: the Ionian Islands (mainly Zante [Zakinthos] and Corfu [Kerkira], Dalmatia as well as in Venice herself where a big Greek diaspora lived. The number of icon-painters registered in Crete’s main town, Candia (Iraklion) speaks of the scale of that activity: 90 painters for the period 1450-1500.

Depending on their client Cretan icon-painters could do icons either in the maniera greca or in the maniera italiana. When working for their Catholic customers they satisfied the needs of a conservative circle of clients who held firmly to the tradition and therefore their works were made in the style of the 14th-century Tuscan and Venetian masters, i.e. their painting is based on patterns borrowed mainly from the Late Gothic and, to a much lesser extent, the Renaissance art. Indications of their knowledge of Western patterns can also be found in the icons created for Orthodox Christians but they remain subtly intertwined into the entirely Byzantine feel of their works. The icons in Byzantine style followed the highest achievements of art from the time of the Palaiologos. As early as in the late 14th century and early 15th century in Crete this art was fuelled by masters who had arrived from Constantinople. In Crete they left not only their icons and miniatures but also murals (the churches of the Presentation of the Virgin in Sklaverochori; Panagia in Meronas, Amari; Panagia in Kapetaniana (1401)).

Andreas Ritzos, J(esus) H(ominum) S(alvator), (sec. half of the 15th c.), Byzantine Museum, Athens (after M. Acheimastou-Potamianou)

As at mid-15th century the great demand for Cretan icons led to the emergence of a generation of talented icon-painters as the names of Angelos Akotantos, Andreas Ritzos and his son Nikolaos, Andreas Pavias and Nikolaos Tzafouris stand out among them. They left a lasting trace in the art of the period not only because of the quality of their works but also because of the development and establishment of new topics and compositions such as the Embrace of the Apostles Peter and Paul, Christ the True Vine, Christ the Great Archpriest, etc. among them.

Probably, mural painting at churches on the island, as a less lucrative job, remained to the side of the occupations of the great masters of icons. Quite expectedly, in the second half of the 15th century the mural ensembles created on the island decreased significantly and their quality was inferior to that of the Cretan icons. There are known cases where icon-painters coming from Continental Greece were commissioned to do such murals, for example Xenos Digenis of Muhli in Peloponnessos (1470-1491).

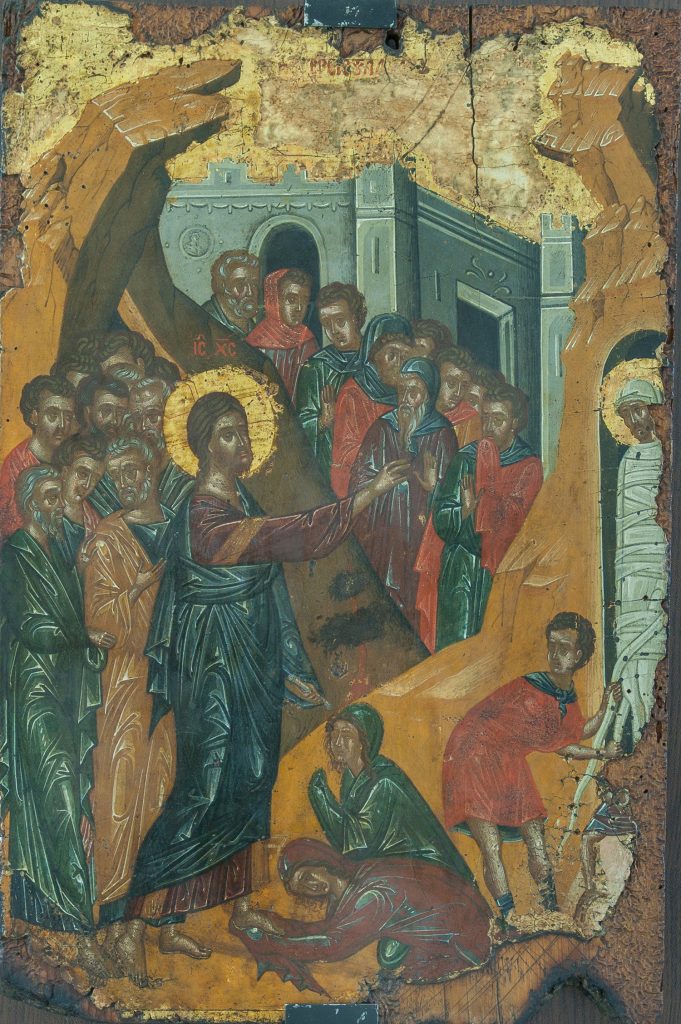

Unknown author, Raising of Lazarus, about 1500, Museum of Christian Art, Sofia

In the 15th century and early 16th c. the Orthodox world accepted the works of the Cretan icon-painters in a varying degree. The two most influential monasteries in the Eastern Mediterranean: Mount Sinai and Pathmos, which preserve to this day big collections of icons by Cretan masters from that period, fully embraced and highly appreciated the quality of Cretan icons. Compared to them, until 1530s the number of icons commissioned for the iconostases of the Mount Athos monasteries (e.g. Dionysiou Monastery) is insignificant. The dissemination of Cretan patterns in continental Greece is also that weak as concerns monuments of wall painting. In this relation I mention again the icon-painter Xenos Digenis, who, after he had painted the Church of the Holy Fathers (Ayii Pateres) in Apano Floria on Crete in 1470, returned to the continent where he created two wall painting ensembles: the Church of the Assumption in Kato Meropi, Epirus and the church of the monastery of Myrtia in Aetolia (1491). They clearly show that the author was acquainted with the Cretan painting from the late 14th century and early 15th century and also with his contemporaneous murals and icons on the island.

It was not until the third decade of the 16th century that the art created on Crete started to spread to the big monastic centers on Mount Athos and Meteora. A factor that was certainly conductive to monasteries turning to these masters is their economic wealth which had significantly increased as a result of the rise of the Ottoman Empire at the time.

The icon-painter who opened the doors of Mount Athos and Meteora, and soon thereafter of the entire Balkan peninsula, wide for Cretan art is Theophanes Strelitza-Bathas. In 1527 he was invited to Meteora to paint the Katholikon of the Monastery of St. Nicholas of Anapafsas. Several years later, he started to work on Mount Athos where he created his most significant works: the Katholikon (1534/5) and probably the refectory (1535-1541) of the Monastery of the Great Lavra. In 1545/6, together with his son Simeon he painted the Katholikon of the Stavonikita Monastery as well as the refectory of the Chapel of Saint John the Baptist of the same monastery. Another talented icon-painter, probably a Cretan, who worked in this period in Mount Athos, is Macarius the Monk. In 1540 and 1541, he painted the Katholikon of the Koutloumousiou Monastery and the Hilandar cell Molivoklisia, near Karyes. Maybe the second most significant Cretan is the icon-painter Zorzis whose name is known only from a note in the typicon of the Dionysiou Monastery dating from 1634. For he did not leave any work signed by him there is no unanimous opinion among the researchers as to which works can be attributed to him and which – to his students. The list of frescoes associated with his name include the Katholikon of the Dionysiou Monastery (1546/7), the old refectory of the same monastery (after 1553) and the murals in the Katholikon of the Docheiariou Monastery (1567/8). His studio in Thessaly was also engaged in large-scale activity: the New Katholikon of the monastery of the Transfiguration (the Great Meteoron) (1552), the Katholikon of the Monastery of Rousanou (1560/1), also on Meteora, and the Dousikou monastery (1557), near Grevena.

Markos Bathas (?), Christ Great High Priest ‘in glory’ and four hierarchs (16th c.), Kamena Monastery, Sarandё (Albania), (after E. Drakopoulou)

According to the great researcher of Cretan painting Manolis Chatzidakis the frescoes in the Katholikon of the Monastery of Iviron (after 1577) made by the hieromonk Marco and the murals in the refectory of the Filotheou Monastery (1561-1574) most resemble the works of the Cretans on Mount Athos.

A great number of icons for these monasteries were made on the spot but there are some presumed to have been brought from Crete – for example the five icons (1542) representing the interior side of the iconostasis of the main church of the Dionysiou Monastery which were made by the icon-painter Euphrosyne as well as the icons from the Feasts tier of the iconostasis of the Katholikon of the Great Lavra attributed to the same icon-painter.

So far, the oeuvres of Theophanes and Zorzis are the best studied ones. While there is almost no information whatsoever about Zorzis we draw a lot of evidence of the life of Theophanes from archive documents from Crete and Mount Athos. The more advanced the studies on 15th-century Cretan painting, the more attention is beginning to be paid to the connection of Theophanes with the works of the famous icon-painting ateliers on the island to such an extent that Euthymios Tsigaridas has suggested that he probably studied at the studio of Andreas Ritzos.

The paintings of Theophanes mix late Byzantine patterns which widely penetrated Cretans’ 15th-century iconography and Palaiologos patterns studied by the icon-painter on Mount Athos – mostly at the Katholikons of the Protaton, Vatopedi and Hilandar. Some iconographic types borrowed from Italian engravings or canvases (the Massacre of the Innocents, the Supper at Emmaus, the Last Supper) also made their way into his repertory although they are of limited quantity and are presented so as to preserve the Byzantine countenance of the image. In terms of his style the main distinctive characteristics of Theophanes’ works are the contained emotions and movements creating the overall impression of tranquility, rhythmicity and classical elegance.

Xenos Digenis, the Church of the Assumption in Kato Meropi, Epirus – St. Nicholas

By his works on Mount Athos Theophanes exerted tremendous influence not only on his contemporaries but also on the next generations of icon-painters. The organization of the mural program has been repeatedly reproduced, mostly the one of the Great Lavra which he probably prepared together with those who commissioned the murals: the Veria Metropolitan (for the Katholikon of the Lavra) and the Serres Metropolitan (for the refectory). The exclusive authority commanded by that monastery conclusively determined the place of the Cretan’s oeuvre in the history of Orthodox art. It suffices to mention just the frescoes at the refectory of the Bachkovo Monastery a century later.

If one has to assess the importance of Theophanes as an intermediary in the dissemination of Cretan patterns on the Balkans, his contribution to their establishment is important beyond any dispute. Nevertheless, the ways of penetration of topics and iconographic patterns characteristic of the Cretans are not at all exhausted by reproducing his works or the works of the other Cretans who worked on Mount Athos and in Thessaly. Undoubtedly, some of these ways go through the dissemination of the Cretan icons which remain among the highest exemplars from the times of late Middle Ages.

Maria Kolusheva

References:

Chatzidakis, M. Etudes sur la peinture postbyzantine. London, 1976.

Garidis, M. La peinture murale dans le monde orthodoxe après la chute de Byzance (1450-1600) et dans les pays sous domination etrangère. Athènes, 1989.

Βασιλάκη, Μ. Παρατηρήσεις για τη ζωγραφική στην Κρήτη τον πρώιμο 15ο αιώνα. – In: Ευφρόσυνον. Αφιέρωμα στον Μανόλη Χατζηδάκη. Τ. 1, 1991, Αθήνα, 65-77.

Εικόνες της Κρητικής τέχνης. Από τον Χάνδακα ως την Μόσχα και την Αγία Πετρούπολη. (Κατάλογος Εκθέσεως, εισαγωγή: Μ. Χατζηδάκης), Ηράκλειον, 1993.

Χατζηδάκης, Μ. Ο κρητικός ζωγράφος Θεοφάνης. Η τελευταία φάση της τέχνης του στις τοιχογραφίες της Ιεράς Μονής Σταυρονικήτα. Άγιον Όρος, 2007.

Tsigaridas, E. Theophanes the Cretan. The Foremost Painter of the 16th Century. Thessaloniki, 2016.